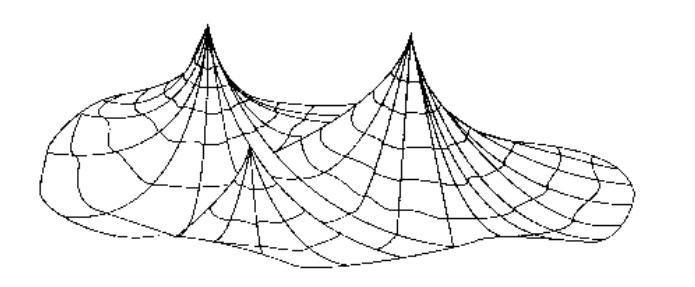

April and May have been very busy months for the Agile Elephant Crew – first client, first conference, first Meetups , first partners signed – and has not left as much time for background research (and hence blogging) to take place. But it is ongoing. One thing we have been doing a lot of work in is the future of Organisations in general. We have been researching where similar initiatives to current theories have occurred in the past, to learn what worked, what didn’t, and what came afterwards. Our first “Lessons from the Past” article was on Ricardo Semler. This second one is about previous attempts at non hierarchical workgroups, specifically Quality Circles and Cell based operations, as they were a precursor to all the pods/peletons/holacracies/fishnets* (see diagram at top of article)/wirearchies etc. etc. proposed today.

Cells and Circles were adopted with enthusiasm in the 70’s/80’s but many had been abandoned by the late 90’s. The Economist notes that:

Quality circles fell from grace as they were thought to be failing to live up to their promise. A study in 1988 found that 80% of a sample of large companies in the West that had introduced quality circles in the early 1980s had abandoned them before the end of the decade.

It is thus useful to understand why this occurred.

A summary of Circles and Cells

From Wikipedea:

A quality circle is a volunteer group composed of workers (or even students), who do the same or similar work, usually under the leadership of their own supervisor (or an elected team leader), who meet regularly in paid time who are trained to identify, analyze and solve work-related problems and present their solutions to management and where possible implement the solutions themselves in order to improve the performance of the organization, and motivate and enrich the work of employees. When matured, true quality circles become self-managing, having gained the confidence of management. Quality circles are an alternative to the rigid concept of division of labor, where workers operate in a more narrow scope and compartmentalized functions.

Cellular manufacturing, sometimes called cellular or cell production, arranges factory floor labour into semi-autonomous and multi-skilled teams, or work cells, who manufacture complete products or complex components. Properly trained and implemented cells are more flexible and responsive than the traditional mass-production line, and can manage processes, defects, scheduling, equipment maintenance, and other manufacturing issues more efficiently. (This technique was used outside of manufacturing as well)

In summary overall, the initial benefits from these systems were very good, yet over time their effectiveness and efficiency waned and by the early 2000’s they had frequently dropped out of use. We wanted to understand if there were any lessons in this history that may apply to the next generation of non-hierarchical approaches being proposed today.

Quality Circles

The summary below, taken from Wikepedia, is a pretty accurate and succinct description of the issues Circles faced:

Based on 47 QCs over a three-year period, research showed that management-initiated QCs have fewer members, solve more work-related QC problems, and solve their problems much faster than self-initiated QCS. However, the effect of QC initiation (management- vs. self-initiated) on problem-solving performance disappears after controlling QC size. A high attendance of QC meetings is related to lower number of projects completed and slow speed of performance in management-initiated QCS. QCs with high upper-management support (high attendance of QC meetings) solve significantly more problems than those without. Active QCs had lower rate of problem-solving failure, higher attendance rate at QC meetings, and higher net savings of QC projects than inactive QCs. QC membership tends to decrease over the three-year period. Larger QCs have a better chance of survival than smaller QCs. A significant drop in QC membership is a precursor of QC failure. The sudden decline in QC membership represents the final and irreversible stage of the QC’s demise

One of the big problems with Quality overall is that inconvenient messages of failure often get the messengers shot by embarrassed powerful people in sales, operations and finance. Quality Circles, multidisciplinary by nature, had no one powerful person who was a natural sponsor, so they needed a high degree of top management involvement (read: protection) to ensure they could survive the slings and arrows.

The other problem Quality Cells hit over time were newer, shinier fads came along – and thus these Circles were dropped as the newer fads needed crewing up, as the same workers had to be involved to make the new Thing work, so the Old Thing was dropped . That the new fads were more sympathetic to more traditional hierarchies didn’t help the cause of circles.

Cells:

The biggest challenge when implementing cellular manufacturing in a company is dividing the manufacturing system into cells. The issues may be conceptually divided in the “hard” issues of equipment, such as material flow and layout, and the “soft” issues of management, such as upskilling and corporate culture.

The “hard” issues are a matter of design and investment. The entire factory floor is rearranged, and equipment is modified or replaced to enable cell manufacturing. The costs of work stoppages during implementation can be considerable, and lean manufacturing literature recommend that implementation should be phased to minimize the impacts of such disruptions as much as possible. The rearrangement of equipment (which is sometimes bolted to the floor or built into the factory building) or the replacement of equipment that is not flexible or reliable enough for cell manufacturing also pose considerable costs, although it may be justified as the upgrading obsolete equipment. In both cases, the costs have to be justified by the cost savings that can be realistically expected from the more flexible cell manufacturing system being introduced, and miscalculations can be disastrous. A common oversight is the need for multiple jigs, fixtures and or tooling for each cell. Properly designed, these requirements can be accommodated in specific-task cells serving other cells; such as a common punch press or test station. Too often, however, the issue is discovered late and each cell is found to require its own set of tooling.

The “soft” issues are more difficult to calculate and control. The implementation of cell manufacturing often involves employee training and the redefinition and reassignment of jobs. Each of the workers in each cell should ideally be able to complete the entire range of tasks required from that cell, and often this means being more multi-skilled than they were previously. For this reason, transition from a progressive assembly line type of manufacturing to cellular is often best managed in stages with both types co-existing for a period of time. In addition, cells are expected to be self-managing (to some extent), and therefore workers will have to learn the tools and strategies for effective teamwork and management, tasks that workers in conventional factory environments are entirely unused to. At the other end of the spectrum, the management will also find their jobs redefined, as they must take a more “hands-off” approach to allow work cells to effectively self-manage. Instead, they must learn to perform a more oversight and support role, maintaining a system where work cells self-optimize through supplier-input-process-output-customer (SIPOC) relationships. These soft issues, while difficult to pin down, pose a considerable challenge for cell manufacturing implementation”

The issues the Cells had were not, then, just the “hard” systemic issues – or at least these were easier to predict and solve albeit could hit the business case at transition. The really hard issues were the “soft” ones, especially the requirement to have people who could be multi-skilled, whereas a more Taylorist system, with tasks broken down, can use less skilled labour. It would seem that whereas Cells when working properly worked very well indeed, it took more effort to set up and run them, whereas hierarchies have lower setup costs, need less “soft skilled” attention and can still work adequately, even if not properly run. In other words, Cells were high impact but high maintenance, and if they could not get all the inputs right – continually- Cells tended to perform no better (if not worse) than hierarchical systems.

10 Reasons for Success or Failure

In his book “Quality: A Critical Introduction”, John Beckford quotes the example of a western retailer that took almost every wrong step in the book. These included:

– training only managers to run quality circles, and not the staff in the retail outlets who were expected to participate in them

– setting up circles where managers appointed themselves as leaders and made their secretaries keep the minutes. This maintained the existing hierarchy which quality circles are supposed to break out of

– expecting staff to attend meetings outside working hours and without pay

– ignoring real problems raised by the staff (about, for example, the outlets’ opening hours) and focusing on trivia (were there enough ashtrays in the customer reception area).

In summary, our research showed there were also a number of other conditions that also tipped the balance,and in summary meeting or avoiding the the following conditions were essential for success:

1. Need to have top management involvement for them to work

Without top management support and resource allocation they seem to never make it to more than localised “interesting experiments”, and won’t scale or roll out. Over time they are not seen as part of the mainstream way of working and are prone to being disrupted operationally and politically (see point 9 below).

2. Have to be above a certain size/skill level to operate well (enough members)

This applies mainly to Quality Cells – they need a fairly large membership to keep going as people get caught up in other tasks, move on, or run out of creative ideas. Cells more tended to need a flow of new blood to prevent ossification.

3. Members need to be trained to use them (hard and soft tools). Both Quality Circles and Cells have two key requirements:

– People need to know how to use a large number of the tools/techniques they require, and that means they need to upskill from the more traditional Taylorist huge division of labour model

– People need to learn how to manage both themselves and everyone else in a team without a hierarchical structure, to ensure that things get done

4. They will not work if the thing they are trying to do doesn’t work in the first place

Circles and Cells were designed for very specific reasons and tasks, but were too often used as last gasp attempts to solve very intractable problems. You can’t inject quality into poor designs or substandard materials, and a cell approach won’t work for commodity products when Western labour costs are much, much higher than the Far East. All too often they were not given the authority, resources or time to match the responsibility they were tasked with, and so failure was assured.

The main reasons most fail are:

5a. Management kiboshes ideas coming from Quality Cells, especially if it impacts Management

5b. Cells are not given the authority to cover the responsibility they have

(i.e. the premise of both is scuppered from the get go)

6. Natural life – There is evidence that any organisation of people has a “natural life” before it ossifies. People naturally lose enthusiasm and interest after some time as operationally the biggest problems are solved / all ideas are aired/ rewards given don’t match effort put in etc., and the circle or cell ossifies and eventually dies. Given that mesh system require more input from their members, this process hits them harder than hierarchies.

7. Emergence of an internal hierarchy in the Circle or Cell is a real probability as it is natural for people to derive a “pecking order”, and must be managed – if it happens, losers tune out/leave and the people rising to the top in this way are too often not the best for operational effectiveness.

8. No real rewards for doing QC/Cell work well means people don’t have a motivation to do this over the more comfortable status quo (the real killer is to use it overtly as a cost reduction/output increase approach).

9. In a mesh structure, as opposed to a hierarchy, every node must be more fully functional. This quote from Wikipedia sums it up:

“The implementation of cell manufacturing often involves employee training and the redefinition and reassignment of jobs. Each of the workers in each cell should ideally be able to complete the entire range of tasks required from that cell, and often this means being more multi-skilled than they were previously. For this reason, transition from a progressive assembly line type of manufacturing to cellular is often best managed in stages with both types co-existing for a period of time. In addition, cells are expected to be self-managing (to some extent), and therefore workers will have to learn the tools and strategies for effective teamwork and management, tasks that workers in conventional factory environments are entirely unused to. At the other end of the spectrum, the management will also find their jobs redefined, as they must take a more “hands-off” approach to allow work cells to effectively self-manage. Instead, they must learn to perform a more oversight and support role, maintaining a system where work cells self-optimize through supplier-input-process-output-customer (SIPOC) relationships. These soft issues, while difficult to pin down, pose a considerable challenge for cell manufacturing implementation”

The change management programme here, moving from a traditional structure, needs to be huge.

10. Staff, Cells and Circles usually exist within larger hierarchical structures, and there are continual tensions that must be managed. There are many whys and wherefores (see above points), but to use a biological system analogy, in essence the larger organism tries to reject the foreign element and unless there is continual usage of immune-suppression drugs, it will eventually be rejected (unless the whole structure is changed – difficult – or the cell/circle is kept at some distance, which loses a lot of the proposed benefit). The corollary – hierarchies emerging within heterarchical structures – is uncommon insofar as there are so few heterarchical structures, but exceedingly common insofar as the normal evolution for any heterarchy is a hierarchy – initially informal (a “pecking order”), later formalised. This pattern exists from early human settlement to the latest research on work teams and other “flat” structures.

(In)Conclusion

Big picture, its hard to set up and maintain these sorts of Cell/Circle structures for any period of time compared to a hierarchy – they are higher output, higher impact, true – but also need higher setup and input effort to keep the benefits flowing. This is interesting, as in theory a network/mesh is more stable than a rigid structure as it is more effective, flexible and resilient. All the latest organisation models make the axiomatic supposition of mesh superiority for these reasons. Unfortunately the one thing that is not coming through is that these early heterarchical structures were lower energy, stable, or self sustaining in any way (the opposite in fact) – whereas all the research is implying that hierarchies are (far too) stable and self sustaining.

It is very clear that setting up and running these early heterarchies was non trivial. It is also very clear that hierarchies are a comparatively stable state structure (By the way, the Holacracy model seems to look much like a conventional hierarchy above the workcells). Not only that, but where Cells and Circles were set up within a hierarchical milieu, they struggled. The opposite is not true, hierarchies – often initially “pecking orders”, later more formal structures – usually replaced the heterarchies in these cells and circles unless carefully managed.

Arguably of course, these problems above are due to trying to construct heterarchical systems within existing hierarchies, and one should instead rather start an organisation as one means to carry on (the Heterarchical Startup gambit). But will a heterarchy scale up the Dunbar numbers to 50, to 150, to 500 people, as the level of automatic co-ordination reduces? Note there are no examples of large scale Cells or Circle organisations, they all tended to operate within hierarchical structures, mainly defined by the workflow of the underlying enterprise, and typically topped out between the 15 and 50 Dunbar numbers.

Anyway, there is clearly something in these “Heterarchy 1.0” system designs that is flawed, we are not yet clear as to precisely what it is. That is the subject of ongoing research for us, but we believe these 10 lessons are all clearly useful for looking at the new wave heterarchy thinking around today and so we are looking at all the new ideas with the points in mind – but that will be a future post (or probably more than one…)

*Fishnet structures are interesting as they – in my view – point to the probable endgame, i.e. structures that can integrate heterarches & hierarchies.