At the Enterprise Digital Summit I did a sort of Pecha-Kucha style talk on future organisation structures but I thought it may be worth going through the talk in more detail as a blog post as well. In essence, the formal part was to show the research behind 3 hypotheses we were going to discuss:

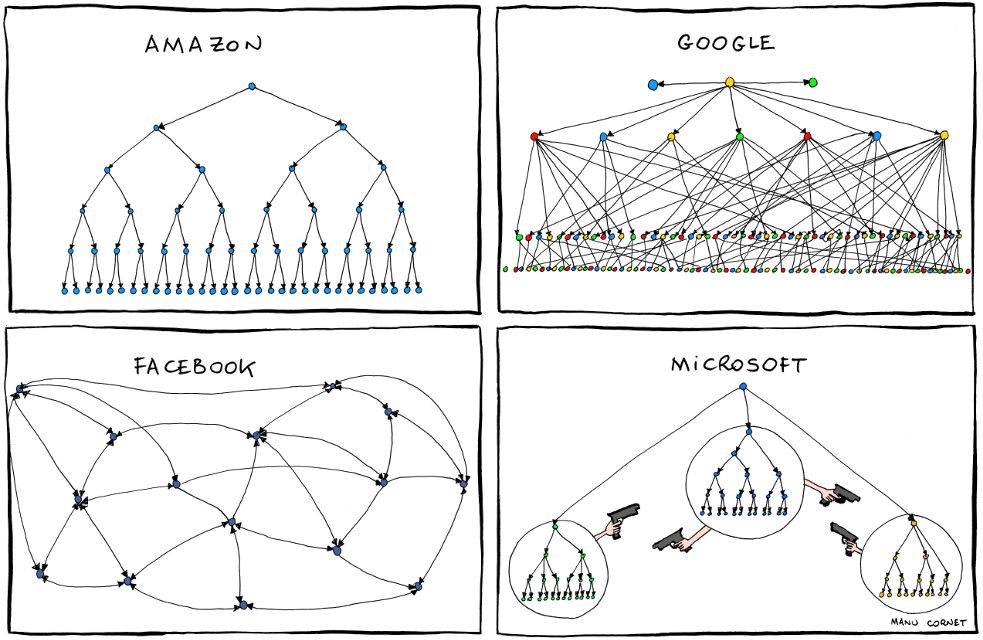

- There are many options for effective organisations, from quite structured hierarchies to very open structures, there is no one “best” option. Some are more appropriate than others in certain situations

- Forget Dunbar’s numbers in any organisation structure at your peril

- Pure Hierarchies are inflexible, flexible Network & Heterarchical organisations have problems scaling and delivering, so the likely “future organisation” solutions are going to be around hybrid structures

Also, we have done a bit of research on long lasting alternative organisation structures, so in the spirit of our “what works, what doesn’t, what’s next” approach, we can make a few observations about modus operandii.

There have been many effective organisational structure options – the ecosystem decides which is “best” (aka “fittest”)

We have gone back into biology and anthropology as well as history to look at organisation structures that work. By this we mean structures that are resilient, effective and flexible – the term we like to use (inspired from here) is Responsive organisations – capable of adapting to new situations. One of the most interesting cases from nature is the difference in societal structure between Chimpanzees and Bonobos – genetically very similar apes to each other (and to humans…), yet one has a hierarchical, patriarchal society and the other is a flatter, matriarchal society. Both are resilient, both are effective (for example both species can use tools), and flexible. The reason for the difference is believed to be the different ecosystems they live in. Another interesting case study is a troop of Baboons that changed from patriarchal to matriarchal society when the alpha males were killed off, and have remained stable in the new state for 3 generations so far.

Also, Jared Diamond’s* and others work on early human societies show that there has always been a wide variety of human ways of organising society. And again, the explanation for differences is usually the environment they are in. Human evolved a more flexible social structure than Chimpanzees or Bonobos, which ultimately has led to 9 billion of us.

As far as organisational structures go, we noted the extremely long lives of various hierarchies – the Catholic Church, Byzantine government, various flexible military organisations, to give a few examples. We also noted that modern corporate hierarchies were modelled on old 18/19th century military structures, but the modern military has in many ways moved farther away from that model than most organisations have, due to the pressures of combating asymmetric armies.

Forget Dunbar’s Numbers at your peril – scale drives hard choices

As we have explained before, there is more than one Dunbar’s number. Dunbar’s work shows that we can only hold a limited number of people at various levels of social closeness. Very close is about 5, close is about 15, general friendship group about 50, and casual friends/acquantances about 150. The amount of social transactions required to keep a person at a particular level rises as they become closer, and we have a limited capacity. To keep 150 people at the level of intimacy you keep 15 would take take all the spare time in a day. Larger groups become ever more distant.

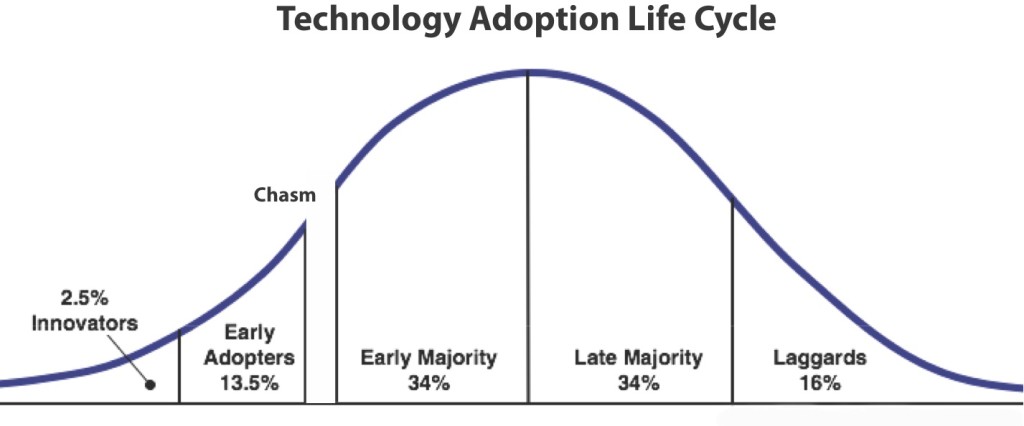

In a social business context, this has a real impact. The level of extreme collaboration that a close team like a work cell requires tops out at the Dunbar number of c 5, it’s very difficult to run teams where everyone knows what is going on at sizes greater than c 15 people, and at c 50 people there is a transition from one person being able to run an organisation, and it has to be split between subordinate managers (this is a well known problem in startups, this is the point where the entrepreneur has to “let go” direct control and put processes in place. In many cases either entrepreneur or organisation don’t survive the transition). At c 150 people up a company moves from being a place you vaguely know everyone to being an “organisation”, where formal structure replaces informal connections.

The reason for this is the amount of interactions required to keep a high level of trust and collaboration. For 5 people, fully connected (networked) to each other, there are 10 links between the individuals in total (20 if you count each part of a link as a 2 x 1 way interactions). At 15 people it is 105 links, at 50 people 1225, at 150 people 11,175. This is a power law, every time the group size increases by 3x, the number of links increases by the square (The law is (N(N-1)/2 to be precise). You can model this to show that fully linked groups rapidly become unsustainable as they scale.

To scale therefore, there are two options

(i) reduce the quality of the links, and as Dunbar explains, this already occurs as social groups scale – but so does their functionality, and therein lies the rub, for more co-ordinated activities (like business activities) to happen the links have to operate at a certain minimum level of functionality; or

(ii) reduce the number of links required. The way to do this is to introduce a structure where not everyone has to link to everyone else. The simplest way of doing this is to introduce a hierarchical structure, where everyone knows their place in it and who they link to. Arguably hierarchies also reduce the number of links which are fully bi-directional, further reducing the load.

This is why human enterprise in any form, when it scales, throughout history has moved to forms of hierarchical structures, almost irrespective of surrounding environment. That they are imperfect is not in doubt, but throughout history hierarchies have been, to paraphrase Winston Churchill, the worst form of organisation, except for all the others. In fact, the only really notable thing about any alternative structures so far has been their relative rarity and short lifespans. (There are also a few interesting features of the ownership structure of such stable alternatives which we go into further down the page)

The argument today is that modern working conditions – a sped up business cycle, ability to work anywhere, anytime, increasing need to inovate to compete, plus new technology will force a shift from the hierarchy, and that technology will facilitate this shift to other structures, usually postulated to being more networked and heterarchical.

Hierarchies, Heterarchies….. and Hybrids

There are a number of proposed alternative structures around at the moment, mostly based around networked and/or heterarchical principles. Although these terms are often used interchageably, they are not quite the same.

Networks are the structures that connect people together, strictly speaking any connection structure is a network, including a hierarchy. But by “network” most proponents of new organisations mean a non ranked, non hierarchical structure that connects all to all, and argue that new technologies allow a more flexible way of linking people digitally.

Heterarchies are “a system of organization where the elements of the organization are unranked (non-hierarchical) or where they possess the potential to be ranked a number of different ways” – they differ from the above network definition in that “ranked in different ways” term. The idea is that any individual is differently connected to a variety of networks.

But given the limits of Dunbar numbers and link scaling power laws, how will this work? All the above comments about Dunbar numbers and scalability still apply to these networked structures – it’s not really a technology issue, its a human cognition issue. The flooded inbox problem is a symptom of being over-networked in a business sense, and newer technology doesn’t solve this – companies are finding that as email use declines, the social messaging overload grows – increasingly companies are asking how to filter business social messaging for relevance. In other words, how to impose a link-reducing structure on information flow.

Arguably a heterarchy is more scalable than a pure network, as it allows one to drop a lot of unnecessary links so in effect not everyone is connected to everyone else – in effect forming a scalable small world network structure. However, that starts to look suspiciously like a hierarchy if all links are equal, but some (those that link between the various sub networks – small worlds – for example) are more equal than others – which they tend to become.

Both these new models also require more energy to maintain than a hierarchy, the transaction costs required in maintaining these informal structures require higher time investment and personal skill levels, so at the minimum there usually needs to be a lot of education of people to work in them. There is some concern that not all people or jobs can work in this way, so they limit the labour they can use.

But Hierarchies have also adapted, implementing some features of network and heterarchical practice, and in watching this adaptation we believe the eventual endgame is taking shape – a hybrid structure. For quite a few decades Hierarchies have been trying a number of approaches to reduce their flaws:

- Breaking up into smaller units within a large structure, wher each unit gets closer to a viable Dunbar number so can opearte withoit overwhelming process.

- Increasing reporting lines across the organisations – “matrix” organisations.

- Implementing hetearchies within the hierarchy – Quality Circles, Manufacturing Cells, Ad Hoc Project teams, “Agile” processes are all examples of this.

- Giving authority to people further down the organisation.

What Works – Alternative Organisations that have scaled, succesfully and sustainably

There are a number of interesting case studies of larger companies that do use alternative approaches and have proven they are both scalable and systainable over time:

The UK department store retailer has been going for over 100 years, and is consistently seen as great for customers and great for staff. In structure its is at first glance hierachical, but with the major difference that every employee is in fact a aprtner, a shareholder in the company at a meaningful level, and this impacts it’s culture and approach. There are however 3 other features worth noting about John Lewis that are important:

- It is privately held, i.e. can focus on long term company goals rather than short term pressures from rent seeking investors

- Stores are “natural Dunbar structures” – they are essentially a large collection of c “150 person” elements, the ecosystem has been sympathetic to reproducing viable sized structures

- It operates at the upmarket (aka higher margin end) of its business ecosystem, where a focus on service generates more benefit than possible higher costs of its approach

Gore has been going for c 60 years and pioneered an Open Allocation organisation (choose what you work on, within bounds) structure based on it’s founder’s experience with ad-hoc task teams in hierarchical structures. Gore has c 10,000 associates (employees) in operations spread across the world. It looks to be poles apart from John Lewis, but Gore has some interesting features that are similar:

- Family, then privately owned

- Gore Plants also have limits to size – In each factory they limit the number of employees to c 150 people (recegnise thet number?) so that “everyone knows everyone”.

- At the high end of it’s business ecosytem, again a focus on customer service yields a larger benefit than on cost

Toyota was founded just before WW2, but like most Japanese companies had to re-invent itself afterwards, and developed a system to optimise the conistions of austerity in post war Japan. It became well known for this “Toyota Production System” as the exemplar of “just-in-time” production. The system focussed on minimising slack resources, and emphasized efficiency on the part of employees, and gave a lot of power to the employees on the front lines. They pioneered work cells, quality circles and modular structures. It was the go-to case study in the 1970’s & 80’s. During the 1990s, Toyota began to experience rapid growth and expansion, largely due to the culture. Expansion strained resources across the organization and slowed response time, and the organization culture became more defensive and protective of information. Toyota’s CEO, Akio Toyoda, the grandson of its founder, noted that “I fear the pace at which we have grown may have been too quick.” Note that it maps to Gore and John Lewis in that i:

- Is Family owned

- Although a mass market player, it strove to be at the “high value” end – quality and customer choive were built in from the design process

- There is no direct linking to the 150 “Dunbar Number” but they certainly understood small team dynamics very well, and the “respect for people” philosophy echoes a lot of the thinking of the other two

- Although it does not have the common ownership model of the other two, it does benefit from teh Japanese company corporate loyalty model, arguably an equivalent approach in terms of aligning interests

A number of new companies are often posited as being examplars of these new ways of working (Valve, Medium etc) but as most are new we can’t tell whether they are sustainable. Also, most of these organisations are still relatively small, few are over 50 employees in size, never mind 150, so in Dunbar terms these organisations can work mainly because of human cognition capacity rather than any new structure per se. Also most are almost pure “knowledge busineses”, which have already shown over the last few decades that they are fairly easy to run in less hierarchical fashion . The interesting thing will be to see what happens when they scale, and if there are any ecosystem factors underlying the successes (or failures).

Of the current crop of new organisation experimemts, the one that interests us most is Zappos, as unlike many of the others held up as exemplars today, who are mainly too small and new for any conclusions to be drawn, Zappos is already a larger enterprise that is trying to re-engineer its culture, and it deals with physical materials and operational issues.

Two years ago Zappos stated to implement holacracy, an approach originally based on Sociocracy, ostensibly a heterarchical system but one which has a very structured approach to the ranking of people in different ways (to the extent that sceptics observe that it looks very much like a hierarchy in all but name…).

Zappos differs from our sustainable case studies in a few ways:

- It is not family/privately run, being acquired by Amazon

- It is not clear if it has the common ownership model (at a level that makes alignment of interest top of mind), so it is up to the holacracy culture to deliver this.

- It is not “upper end” of its market, however it is obsessive about service and was an early adopter of the online channel, and can offer a huge range of niche sizes and products that are hard to find in conventional stores

So far the results are unclear, reports lauding and lamenting it both appearing in the media to date, but it’s early days and major change is never quick – definitely a cse study in the making.

What Doesn’t?

We have written already of why many earlier structures failed (see here) and have noted that all succesful organisations tend to have in them the seeds of their own destruction, but the following amusing – and educational – concepts are also worth following up on, as they will kill any organisation, no matter how structured:

- Peter Principle – every employee rises to their level of incompetence

- Parkinson’s Law – make-work expands to fill the time available for its completion. There will be the maximum number of chiefs at the point the system collapses

- Pournelle’s Iron Law – in essence that in any organisation, the people who will eventually rule it will optimise for its own survival, regardless of whether it is functional or not

What’s Next?

This was to be the rest of the workshop – publish a comment and damn the torpedoes!

*Some in the Anthropological establishment dislike Diamond’s work, its hard to tell whether its valid objection or noses out of joint, but what is unarguable is that he shows that various succesful early human societies can be organised very differently