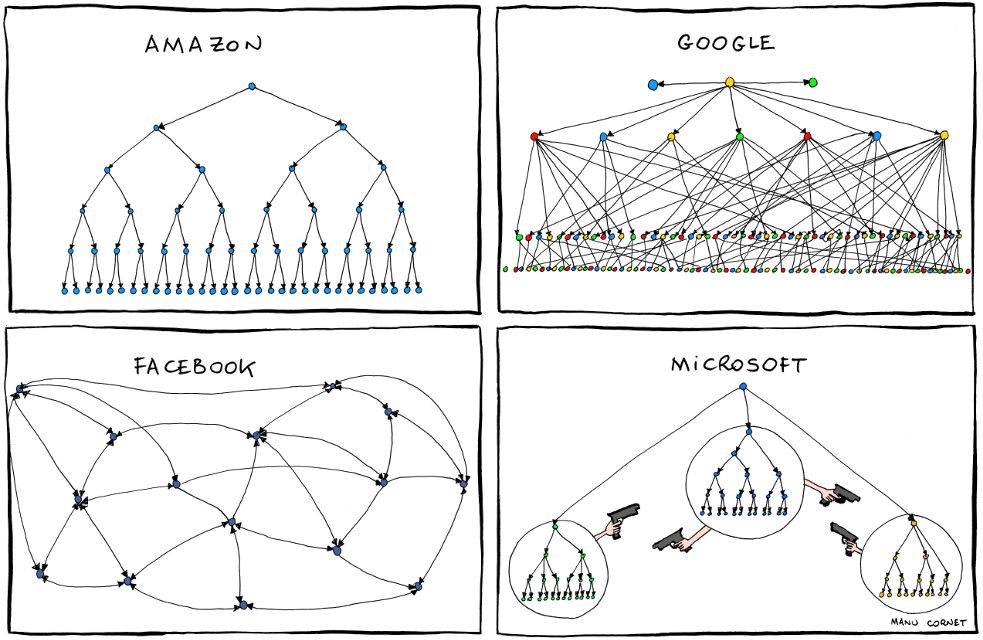

(Cartoon above courtesy Manu Cornet at Bonkersworld)

There are many thoughts about the Future of Work these days, and many suggestions of how companies should respond – advice abounds on how to structure a business for example, from tinkering with the way people are treated in hierarchies, to new structures, to dispensing with hierarchy altogether. Working out which (if any) of these new Ways of Working are likely to succeed is non trivial, but may we propose an approach as a first cut?

There is a fairly arcane principle in System Dynamics (and other branches of probability modelling), known these days as the Anna Karenina Principle (aka AKP) after Tolstoy’s observation that:

Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.

In essence it is the principle that, for any complex system, multiple factors are required to go right for success to occur, but it only has to fail in one key factor to be non-optimal or even useless.

It was renamed the Anna Karenina Principle after Jared Diamond’s book Guns, Germs & Steel used it to explain why so few animal species of all those that exist are domesticated. In short, many traits are needed to make an animal domesticable, any one of which if failed means the animal is not suitable – for example the Zebra, whose equine counterparts in Eurasia were domesticated, are such ornery beasts that it has proved impossible to domesticate them (probably been around humans longer than all the others…).

A corollary is what I call the Reverse Murphy’s Law Principle – Murphy’s Law says “If something can go wrong, it will go wrong”. The Reverse Principle says “For something to go right, nothing must to go wrong all the time. i.e. even partial success is often not enough. This is also known as the “The Principle of Fragility of Good Things” .

The principle can be seen at work systemically in the early frothy days of innovation of a new technology. Take any you choose – say aircraft, or ships, or PC’s, you choose – and the early days of the New New Thing’s evolution sees all permutations and combinations of approaches, some fail fast, others linger on but eventually only those with the minimal failure modes remain. And it doesn’t take much. For example, before the iPhone and iPad was the Hewlett Packard iPAq – it did everything the first Apple products did, and more, but it failed on one key feature – it, like all it’s generation of mobiles that had IP capability and were smart, had a frustrating user experience, so it failed. (OK, you could argue that it wasn’t beautiful either, but I contend if it was easy to use a lot of sins could have been forgiven). In general the AKP principle would argue that the early failures failed in multiple ways, survivors had fewer failure modes and were weeded out as their fewer shortcomings showed themselves over time.

Anyway, applying the AKP principle to a comples ecosystem like an organisation is possible and also, as noted by the University of Leicester looking at organisational behaviours in stock crashes, allows some levels of prediction

…[Analysing] the dynamics of correlation and variance in many systems facing external, or environmental, factors, we can typically, even before obvious symptoms of crisis appear, predict when one might occur, as correlation between individuals increases, and, at the same time, variance (and volatility) goes up. … All well-adapted systems are alike, all non-adapted systems experience maladaptation in their own way,… But in the chaos of maladaptation, there is an order. It seems, paradoxically, that as systems become more different they actually become more correlated within limits.

It has also been used to explain the emergence and long survival of the peer review process in academia, modern Marketing techniques, and, of course, social networks. So, applying this principle to new Ways of Working is a valid approach.

Now to be fair, in real world multi-factor complex systems, the sporadic failure of one subsystem is not enough to bring it down, specially if redundancy (ie routes around the broken system) are available. The bad news is that redundancy has an operating friction and cost all of its own, which is a mode of failure in some situations. So the question is – what are the factors that will drive failure

First, it’s worth looking at what exists today to see what has worked so far – the hierarchy. The mere fact that it exists, and has for a very long time, says it is successful as a mode of organisation structure. In the evolution of ways we organise ourselves, hierarchy was an early approach and a venerable survivor of the dangerous plains of the fitness landscape of human organisational structures. There are clearly inefficiencies in the system – Parkinsonian ossification and Peter principled incompetence for example – and tweaks in modern times have included matrix management, attempts at some form of upwards influence, creating hybrid structures (e.g. work cells), structured inefficiency to obtain engagement (e.g job enrichment).

It is argued that the hierarchy is no longer fit for purpose, for a wide variety of reasons across the board – from being too slow to respond to strategic pressures, too ossified in its structure and systems, culturally unability to attract, retain, engage & motivate the right people, move knowledge through the organisation, and (silo syndrome), too prone to internal inefficiencies, the digital transformation (and Coasian transaction costs) will do for it….there is a long list of reasons for impending doom. But in essence it fulfills the AKP for organisation structure today, there is as yet no disastrous mode of failure and a long history of survival.

What is less clear is what can replace it, and whether they will actually be better – and this is where we think the AKP comes in.

Most of the newer contenders involve more heterarchical (non-hierarchical) ways of working, from the very structured, based on Sociocratic principles (e.g. Holacracy) to the almost chaotic (e.g anarchy as organisation ) and many flavours in between. But these are all largely unproven – examples have occurred in the past but they have generally not been adopted by competitors – more the opposite case in fact. How can one have any confidence of success, and is it possible to differentiate the potential of the various approaches?

What does the AKP principle imply for them?

One approach is to think of the potential key modes of failure, any one of which will bring an enterprise to its knees. The literature abounds, but putting a systemic hat on, one could look at a set of modes of failure of an enterprise end to end, and list them in some order of importance – or at least when they are encountered Here is a “Starter for 10”

- Create a desirable product or service (clearly if you can’t do this, there is no enterprise)

- Market and sell this into a competitive environment (build a better mousetrap, and….)

- Source and/or manufacture and deliver a working product or service into a competitive envelope of cost, time to deliver, and quality (amateurs talk strategy, professionals talk logistics)

- Service and support existing customers to retain them (cost of new customer acquisition >> costly than existing clients)

- Attract, retain and motivate the right people at the right price (high staff turnover = lost turnover and high costs)

- Create a culture that at best motivates these people to their highest levels of engagement (or at least prevents too much free riding and other parasitic behaviours that destroy group cohesion).

- Continuously improve the core capability to maintain competitiveness (Do Things Right) but also….

- ….Sense the winds of change, keep on innovating to maintain product desirability, and change strategy and operation in time to avoid obsolescence – “Do The Right Things” in the parlance of leadership theory….

- …while still being Agile enough to shift position to face new realities (Even the best strategy fails at first contact with the enemy)

- Finally, deal with large and sudden shocks to the system sufficiently well to live to fight (or at least trade) another day (Don’t let the Black Swan’s cr*p on you…)

Applying this “10 Factor Test” should give some interesting answers, so this is a “first cut” approach we will be using to analyse the various “New Ways of Working” theories currently abounding vs the venerable old hierarchy going forward. Of course, to ensure we don’t suffer from survivor bias, its is also necessary to look at hierarchies over time to see what factors have caused failure in the past and been dropped. That will be the subject of the next post in this topic.