Last Wednesday night we had our September Social Business Meetup, with Euan Semple being our speaker for the evening (he spoke on Pigs, Lipstick & Dinosaurs – see our summary here, and his relevant blog posts his relevant blog posts here, here and here)

Anyway, in the Q&A&D afterwards, we started to talk about “clicktivism”, and people noted the way Twitter seems to be increasingly being used by people to try and drive “mob opinion”, and even signal they are “more X than thou”. I have seen the effect, and it does seem to be an increasing “thing” on Social Media – but I can’t prove it as it’s very hard to write algorithms to sort genuine opinions from these, so I started looking for a reason as to the “why”.

So, I was scrabbling round the Web to see if there was any information on this, and one term I came across was “Virtue Signalling” and that made me realise that this was covered already in a classic piece of game theory in signalling “weak tells”.

In Game Theory, you can signal an intent – a “tell” in the parlance – that may or may not be genuine. The way you tell if the “tell” is genuine or not is to measure its strength, and this is measured as the cost to the signaller. A “strong tell” is typically by someone who will “put their money (or other assets, reputation, time etc) where their mouth is”. A weak tell is a signal with little cost to the user.

In general, weak tells are easy ways of generating a lot of traffic – they are, for example, the method of choice for “clicktivism” – a low cost of supporting something with little comeback. Facebook “Likes” are a simiar example of a Weak Tell. I did an analysis on my Broadstuff blog of how this plays out in Social Media, especially about making it harder to measure true intentions and sentiment.

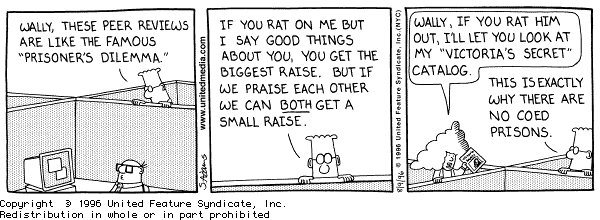

From an Enterprise point of view, as well as making it harder to discern meaning on social media that one may be monitoring, this has an impact on internal social business systems as well, given that similar conditions apply. (And then there is the impact of payoff distortion by non-business goals, as the Dilbert cartoon above notes). But in general, “Virtue Signalling” has 3 main effects:

- Exaggerates a particular (popular, or advantageous) view

- Puts off potential for disagreement

- (Possibly) allocates social capital to the wrong people

The net-net is that certain arguments are overplayed, certain arguments are not made as hard as they should be, and possible the wrong people get allocated resources or authority. This can have a negative impact on performance – studies have shown that suppressing dissent can drive hidden costs such as wasted and lost time, reduced decision quality and decreased engagement/motivation.

To be fair, this is hardly a Digital “thing”, this has happened in organisations from the start. The risk with electronic media though is that the effect is amplified, so the question is how to prevent it. In face to face environments, it is usually the role of a moderator, facilitator or chair to ensure that all voices are heard, but how does one replicate that on a business’s social communication systems? Some thoughts:

- Good news – the “mob storm” effect is likely to be far less intense, so less social pressure to say nothing

- More Good News – unilike public social systems, it is possible to “set a tone” on a private network that just cannot be achieved easily on more public ones

- There are a number of approaches that have worked in allowing a wider set of views to emerge, from suggestion schemes to “rewarding dissent” policies (this is quite a good brief summary from Wikipedia) – all have plusses and minusses, and seem better or worse in certain conditions, but it can be done.

- However it takes design and ongoing dedication to ensure the network can welcome and handle dissent and unpopular views

- Chances are, it also needs some form of moderation on occasion, albeit thse can be voluntees rather than full timers

Something to be aware of, at any rate….